Is “The Shift” Bad for Major League Baseball?

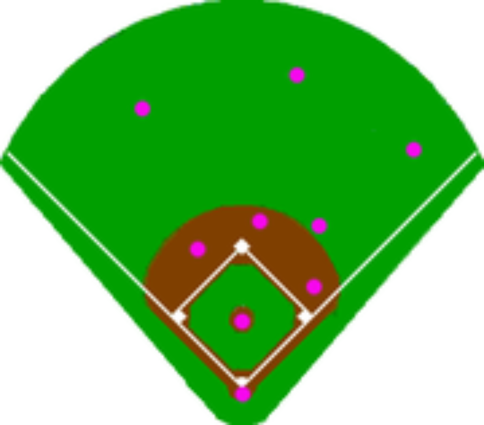

Critics of today’s brand of baseball oft decry defensive shifts (“the shift”) and other changes in teams’ strategy. Its defenders may point out that the game is, well, different from how it used to be. Certainly, there is more of an emphasis or appreciation of the business aspect of baseball operations and rivalries between players of different teams are less likely to spill off the field. But, the on-field product has shifted as well.

Even for those of us who approach baseball from a more statistics-oriented mindset, though, concerning the shift, there are people who favor the use of shifts and those who don’t. To me, it just looks like a lot of extra movement I wouldn’t want to have to do if I were playing. That may speak to my present level of fitness more than anything.

Independent of our lack of conditioning, the major issue here is whether the shift, with all of its non-tradition and aesthetic disruption, is effective in achieving what it’s set out to do. We don’t yet have a wealth of data on how shifts impact games. There’s still a bit of a disconnect between how often shifts are employed and their impact in depressing offense.

As stats are compiled and interpreted, though, the early returns begin to tell a story. This story complicates what we think we know about the shift. When we assess how the shift impacts offense, we must sift through the micro-events, which may fluctuate in efficacy, to find the macro-level effect. Just as the shift’s efficacy can vary, our feelings on the benefits of shifting might similarly swing.

The shift cuts down on singles, but not runs

Russell A. Carleton has written extensively about the shift for Baseball Prospectus. His article from May titled “How to Beat the Shift” explains in detail what the Statcast data culled from Baseball Savant, a site offered by Major League Baseball, reveals. As Statcast shows, BABIP and singles go down in relation to the shift, with the “full shifts” even more effective on that front than partial or “strategic” shifts.

As Carleton points out, though, lower BABIP and fewer singles aren’t the same thing as outs accrued. To account for walks, he used the newfound ability to look at defensive shifts as they impact expected vs. actual on-base events. Regarding the full shift, from 2015 to 2017 (the available data period), there were 493 singles fewer because of the modified alignment, but 574 additional walks issued. In other words, teams appear to be robbing Peter only to walk Paul.

And what about extra-base hits and homers? While, again, there are differences to be found between full and partial shifts, in opposition to Carleton’s hypothesis that the shift depresses slugging and power, the results borne out by Statcast suggest an uptick in these outcomes. The net effect is, on average, that teams lost 3.5 runs a year through defensive shifts. In short order, it’s becoming evident that the shift may not be all it’s cracked up to be.

To be fair, it is not as if all hitters fare better against the shift than might otherwise be expected. For players in the mold of Chris Davis, who see a full shift 250 times or more during the season, the shift increases singles dramatically but reduces the number of all other outcomes. In doing so, it decreases the number of runs allowed by a team on defense.

In contrast, for all other groups, the number of actual runs increases relative to expected runs. Across analyses and when mapping batter and pitcher outcomes on top of one another, Carleton finds the shift generally dampens singles, has a negligible effect on other hits, and drives up walks. It’s not really reducing offense. It’s just, ahem, shifting the blame from singles to walks for allowing runners on base.

As a function of these observed effects, Carleton recommends that shifts be used only in certain cases, i.e. when facing extreme pull hitters like Davis. His aversion to over-shifting is not a personal or sentimental one, but one informed by statistical models and analysis. As Carleton acknowledges, he’s “just not so sure it actually works.”

Rob Manfred vs. the shift

OK, so the shift may not be as effective as some teams would like. Before we get to why it may not be working as designed, let’s consider the question at the heart of this piece: Is the shift bad for baseball? It’s a rather open-ended question.

First of all, how do you define “bad?” Isn’t that subjective? Well, yes, it is subjective. If we look at Major League Baseball’s list of priorities in recent years, though, we might gauge how the league regards defensive shifts. From Day One as MLB commissioner, Rob Manfred has expressed an openness to banning extreme shifts based on the impression that they might create an unfair advantage. More recently, he indicated that the MLB competition committee is actively discussing regulating defensive shifts.

Manfred and others close to the game have expressed a desire to speed up the game of baseball. This desire may frivolous, especially when we compare baseball to the experience of watching football, a sport replete with timeouts and other stoppages. Nevertheless, the league has restricted the number of mound visits that teams may make, and it continues to toy with the idea of implementing a pitch clock. In short, pace of play is a concern for Major League Baseball.

Is loving the shift irrational?

Sam Miller, in a column for ESPN.com, references Carleton’s findings, reiterating that the shift is not saving runs. He also specifically addresses Manfred and Co.’s stated opposition to extreme shifting. In doing so, Miller delves into why the shift may be failing, a topic Carleton likewise considers.

Both writers speak to a discomfort felt by pitchers relating to defensive shifts. Many of them may not actually pitch to the shift, but rather pitch around contact, trying to nibble at edges and corners of the strike zone. This is to say that pitchers might, er, balk at throwing strikes in relation to the shift, leading to undesired results.

Is the modern insistence on shifting therefore irrational? In the case of the Houston Astros vs. Joey Gallo, it can indeed be very hard to figure out. As Miller notes, meanwhile, for some teams, the shift is not held in very high esteem. In addition, teams may simply be convinced they can make the shift work. It might just require the commitment and execution by the pitching staff, or be dependent on the ability of each staff to manage pitching to the shift.

The shift isn’t as “boring” as some think

That’s Miller’s contention, anyhow. To the extent that pitchers can’t feel comfortable, balls aren’t put in play, and the pace of the game slows, defensive shifts might reasonably be deemed “bad” because they are not as exciting as putting the ball into play.

If pitching staffs do begin to adjust, though, perhaps MLB’s fuss over defensive shifts might be much ado about nothing. After all, opines Miller, defensive shifting isn’t making the game as boring as Manfred and Co. might make it seem. He writes:

For now — and beyond the basic question of whether it’s at all appropriate for the league to legislate basic strategy like this — baseball’s most fallacious assumption isn’t that a defensive strategy that apparently boosts offense is actually crushing it. Rather, it’s that the shift is somehow making baseball boring, more monotonous.

In fact, it has added variety and mystery. Teams are finding their own strategies, gambling on these strategies, tinkering with these strategies, differentiating themselves from their peers with these strategies, and then challenging hitters to adapt with their own individual strategies. They’re doing it all visibly, on the screen, so we have something to talk about — and, even with mountains of data, something to disagree over.

Rather than vilifying the shift, Manfred should be broadcasting the ambiguities of it. He should be emphasizing each team’s unique approach to it. The shift might or might not be working. But it isn’t boring.

I tend to agree with Miller’s assessment that the shift has given us plenty to talk about and debate. In this regard, it isn’t inherently boring. That said, I’d like to see teams use the analysis of people like Russell Carleton and the shift more effectively. It’s one thing to have “boring” baseball. It’s another to have poor strategy.

Is the shift bad for baseball? Despite the above considerations, the jury may yet be out. Whatever the case, here’s hoping Major League Baseball lets it run its course before trying to intervene.

-Joe Mangano