Let’s End the Infield Fly Rule

Generating more excitement within games is a very common topic in MLB circles. Many feel the length of games overall is a problem, some feel too much time in between pitches is an issue, and others feel that the problem comes from a less aesthetically pleasing version of baseball now that philosophical changes and optimization have resulted in fewer balls in play. To paraphrase writer Joe Sheehan regarding that last point, there’s simply less baseball in baseball games nowadays. Although I have thoughts about improving game length and length of time between pitches, I have a very quick and simple way to increase on-field action: Lose the infield fly rule. It’s a pointless rule from the 1800s that at best stops all on-field action, but often just confuses the heck out of people prior to stopping the action.

I’ve been yelling at this cloud for a long time, and every time I say it, the first response is always something along the lines of “Well, no, you need the rule. Without it, fielders may drop a pop up intentionally to try to get a double play or a force out.”

EXACTLY. In sports, when is action a bad thing?

Currently, when there are runners on first and second and less than two out, and a batter hits a pop-up one of two things happens. The first possibility is that an umpire decides the infield fly rule is in effect, all players involved are aware of the call, the batter is automatically out and all action comes to a screeching halt.

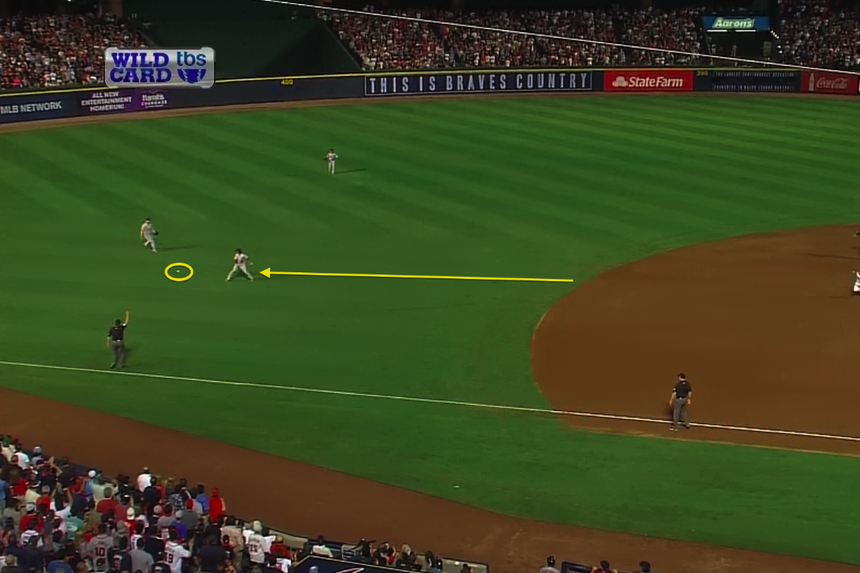

The second possibility is that an umpire makes the call that the infield fly rule is in effect, not everybody is aware of it (sometimes the umpire calling it is on the other side of the field from the baserunners and some fielders, so not all players hear the call) or the ball is so far out in the outfield grass that players assume there’s no way that’s an infield fly. Either way, it ends with players looking around at each other, umpires looking at each other to see who called what, and announcers having no clue what just happened. The end result is once again, zero action. There’s teases of action, some confusion, and ultimately no action.

However, if there was no such thing as the infield fly rule when a pop up is hit, this is what would happen:

Fielders would have to decide that if the pop up comes their way:

- Should they catch it for the relatively easy out

- Let it drop to possibly be able to turn a double play, or a force out (a force out that gets a good runner off the base paths might be worth the risk.)

Prior to the play, all fielders would need to be acutely aware of the game situation – in fact so much so that it would likely have to be addressed prior to each batter. Game inning and game score have plenty to do with the decision-making and weighing the risk vs. reward. The running speed of the batter and baserunners would need to be considered to both evaluate the amount of time the fielders have to make the play, and if exchanging a fast runner for a slower one is worth the risk.

That is a lot of high-level strategy the fielders and baserunners (and the fans!) need to consider. That in itself is fun – that’s what we fans do, we debate the strategies our team employs. Of course, sometimes the fielder in question will simply catch the ball to take the easy out. Yet again, who cares? It certainly had our excited attention for a few seconds while the ball soared through the sky. The runners would likely have to retreat very quickly to their respective bases as they likely were leaning toward the next base in the event the ball was intentionally dropped. (All of which is a better option than wondering which umpire may or may not have called something, then absolutely nothing happening.)

However, if the fielder did decide to let the ball drop in an attempt to turn a double play…All hell would break loose, because let’s be clear: Picking up a ball that had been over one hundred feet in the air, came down like a missile with a heck of a lot of spins and grabbing it cleanly and quickly – is not an easy play. That scenario is far from an automatic double play or force out. Additionally, assuming the ball landed and was corralled, the fielder may not have a lot of time to make a good throw depending on which side of second base they’re on and where the lead runner is. Oh and the runners and the batter? Yeah, you’re not going to have to worry about them “dogging it”, they’ll be running full speed far more often than not when the ball hits the ground.

Regardless of the play’s outcome, at a bare minimum, there’s strategy and anticipation, which is better than an automatic stoppage of play. Yet sometimes, there will be strategy and anticipation followed by action. I don’t think there’s much pushback to the notion that action is better than no action on a baseball field.

If you’re curious (as I regrettably was) as to the origin of the rule, here’s the short version: In the 19th century, when players fielding gloves were smaller than what you and I wear when we’re shoveling snow, the powers that be didn’t want to give the defense an unfair advantage by allowing them the opportunity to turn a double play by “subterfuge”. If you’re curious, subterfuge is a word with usage that peaked in the 1700s. It means deceit. So the logic of the infield fly rule could readily be applied to curveballs and any offspeed pitch hoisted by a a pitcher.

There’s no point in keeping a 19th-century infield fly rule that provides zero benefits to fans watching the game and comes with the express feature of stopping on-field action. More importantly, there’s zero harm to losing the rule in an attempt to create more action. Baseball has survived the horrors of the Designated Hitter and lowering the mound – I think we’ll all recover if pop-ups are no longer automatic outs.

-Jon Rimmer