It’s Time for MLB to Start Implementing Objective Strike-Calling

One of the major advancements in modern day is the use of technologies – whether big or small – to enhance human performance. Some fear that enhancing technology may eliminate certain human jobs. While that may be true in some cases, the pessimistic outlook on technology’s contribution to the human experience is far less fun embracing the possibilities for enhancement of human jobs. The human job of interest here is calling balls and strikes for Major League Baseball games. It’s a pretty good human job; it’s often on TV, it makes pretty good money, and it has the upside of getting to see lots of cities. It’s also a human job protected by a union and labor laws, but I believe designating strikes and balls should no longer solely be a human job – that a more objective strike-calling is both feasible and appropriate going forward.

Throughout baseball’s long existence the sport has been a game played by humans and officiated by humans; nothing more, nothing less. However, with recent advancements in technology, the way athletes train, recover, and even approach the game has shifted baseball into a new age of enlightenment.

It started with teams. The Moneyball story of how a small-market team from Oakland, California used analytical methods to identify undervalued players shattered the way things were done within front offices. However, the story, as captivating and interesting as it was to the everyday fan, was not anything new and ground-breaking to begin with- not even within the baseball world. In fact, Branch Rickey, former GM of the Brooklyn Dodgers, used statistical analysis to form his team back in the ‘60’s. In addition, 20 years later and 20 years before the craze of Moneyball, Bill James started writing his Baseball Abstracts, speaking to the use of statistical analysis within baseball.

Then it moved to game flow. In 2008, baseball introduced instant replay, giving players and coaches the ability to challenge calls; a version of which the NFL has had in place since the mid-1980’s.

And more recently, technology has impacted how pitchers and hitters train.

But the game has yet to embrace technology to improve the way the game’s mechanics work. Baseball has been behind the movement for advancement for years and has always been last to jump on the bandwagon. But time evolves, things change, and new tools allow for more efficient ways of operating; and baseball should do so as well.

Defining the Problem

The history of the strike zone is actually quite interesting. According to MLB.com’s historical timeline, the strike zone was first invented in 1907, with batters only being allowed to have a strike against them when hitting a foul ball. In fact, before 1887, batters actually told the pitcher where to throw the ball! However, since the 1907 inception of called balls and strikes in relation with a confined zone (among smaller changes regarding the edges of the zone), the rule that umpires subjectively call balls and strikes has been around for more than 100 years.

Fast forward to today’s game with the inclusion of technologies like PITCHf/x and STATcast, we can now see the confined outlines of the strike zone on television broadcasts. The audience gets the benefit of the machines’ observations. We can see what really is a ball or not. But, why, if we have this type of technology, can’t the lovely human people on the field use it? You know, the humans who could actually use it to do their job?

Currently, the strike zone is more of a probability assessment rather than a yes or no question. Allow me to explain…

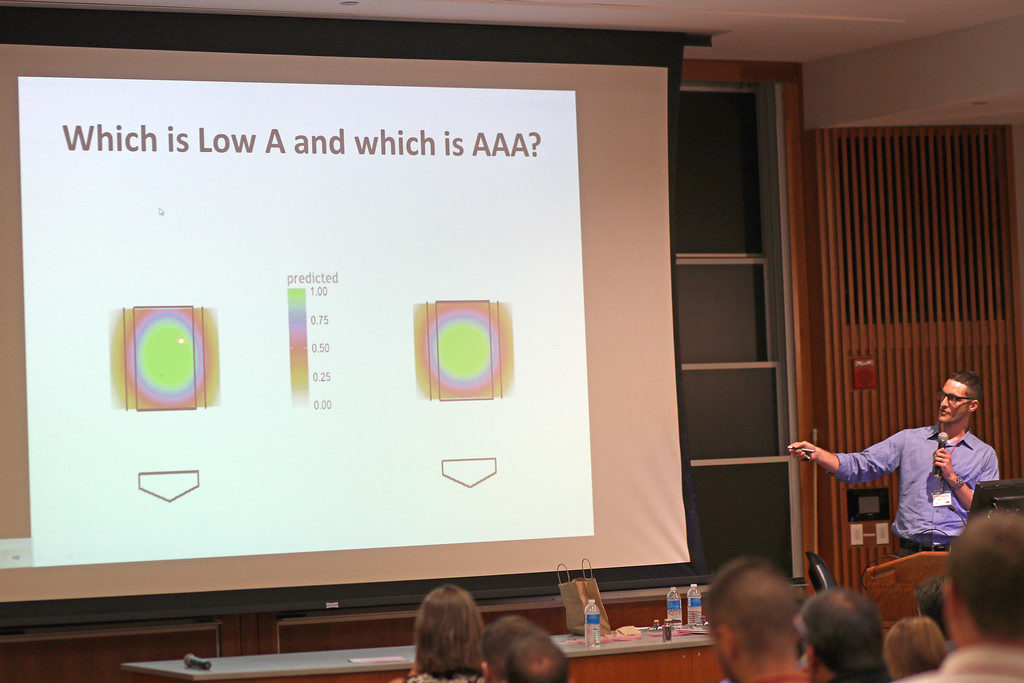

In our review of Saberseminar, I highlighted a talk presented by Nate Freiman. The former player, now Fangraphs writer, spoke about the strike zone throughout the lower levels of play. Specifically, he wondered if the strike/ball calls were worse at the lower levels compared to the higher rankings. Sure enough, they were. However, in addition to his hypothesis being correct, the graph of his findings (pictured below) caught my attention for other reasons.

It’s a little blurry to see, but you can read Nate’s full article here with a much clearer picture of the chart comparing AAA and Low-A strike probabilities.

Referring to the chart, you see the strike probabilities and how they lay inside (and outside) of the confined strike zone. According to the graph, there is a less than 50% chance that a well-located pitch in any corner of the strike zone will be called a strike. Mind you, the data presented was from an accumulation of years worth of Minor League pitches. However, if you look up any contour graph or decide to ever do your own statistical analysis, you’ll find the corners of the strike zone are often missed calls.

Generally speaking, professional umpires do a pretty good job when it comes to calling balls and strikes. However, data suggests that umpires miss roughly about 14% of calls. Moreover, according to MLB.com’s rules regarding the strike zone (Rule 2.00: The Strike zone):

“The STRIKE ZONE is that area over home plate the upper limit of which is a horizontal line at the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants, and the lower level is a line at the hollow beneath the kneecap. The Strike Zone shall be determined from the batter’s stance as the batter is prepared to swing at a pitched ball.”

The key here is: “The Strike Zone shall be determined from the batter’s stance as the batter is prepared to swing at a pitched ball.” From a pure cognitive standpoint, in addition to the fact that current-day pitching speeds are at an all-time high, how can anyone consistently call strikes and balls without error with all that movement occurring in their peripheral view?

What Can be Done?

The question then becomes, how can we objectively get ball and strike calls correct?

The proposal, both presented here and elsewhere, is to provide home plate umpires with a tool that objectively tells them what is a strike and what isn’t. We’ve even had a version of this implemented in an independent league baseball game. Former player turned MLB Network Analyst Eric Byrnes actually called strikes and balls for two games while watching the PITCHf/x technology from afar.

So how would something like this affect the game? One impact that would immediately be felt would be the consistency of the zone. We could transition strikes and balls to a “yes or no”, as opposed to a probability outcome. Pitchers and hitters would probably both appreciate that new approach.

It makes catcher’s jobs easier too. The catcher’s ability to frame a pitch is something that, in today’s game, is increasingly being quantified and valued. Electronic strike/ball calling would eliminate this art as well. Without a proper presentation by the catcher, the optics on a borderline pitch might make hitters un-easy. But, again, measurements and strike/ball assessments occur prior to ball meeting glove. A ball would be a ball and strike would be a strike regardless of catcher action.

While Major League Baseball constantly looks for ways to improve pace-of-play and decrease time spent doing things other than playing baseball, it seems that, in a day where players and managers continually seize game-time to argue balls and strikes, implementation of certain technology to reduce or even eliminate these occurrences could have potential benefits on this initiative.

No one likes change. Especially when a certain way has been the standard for over 100 years. But time evolves along with technology. A movement like this is not supposed to change the game, but enhance it. Technology allows us to operate in a more efficient manner and its presence in baseball is no different. However, how we choose to utilize it – or not – might very well be the larger concern within baseball.

– Mike Lambiaso